I have refreshed my memory: I was thinking of the Funcken book which has a similar reconstruction but according to an article in Slingshot, there is an earlier book called the Roman Soldier (1928) that has a very similar illustration. All of these almost certainly use the same stele that you showed the illustration of. I have seen the stele before but not this drawing of it - the photos of the stele are a bit more difficult to interpret. Sumner's interpretation of the stele is that the funny shorts should be pteruges - and indeed it is obvious that they are indeed pteruges as you can see them at the shoulders. It looks as if the mason has misrepresented the pteruges rather than Roman legionaries wearing such bizarre shorts (they of course do wear shorts a bit later so perhaps the mason mixed the shorts and the pteruges up).

All of which shows that the Airfix figures, though rather funny looking, are sculpted from a contemporary stele (and rather accurately too). Question is: is the stele an accurate image of a legionary?

General

Airfix Romans - Historical Accuracy

13 posts

• Page 1 of 1

Yep, groovy figures indeed were these lads.  Had a couple of sets. Discovered that my Dad's gloss door paint stuck to these figures like glue - mind you it was a bit on the thick side and remember that I painted my archers robes in an amazing deep yellow gloss and their helmets were a kind of burgundy colour. Those archers were and still are my favourite figs in this set. In my battles they downed many a World War 1 German infantryman as well as French Cuirassier as well as their more correct Ancient Briton adversaries. I remember that Ancient Briton chief as if it were yesterday. Love chariot reins. Keep up the good fight!

Had a couple of sets. Discovered that my Dad's gloss door paint stuck to these figures like glue - mind you it was a bit on the thick side and remember that I painted my archers robes in an amazing deep yellow gloss and their helmets were a kind of burgundy colour. Those archers were and still are my favourite figs in this set. In my battles they downed many a World War 1 German infantryman as well as French Cuirassier as well as their more correct Ancient Briton adversaries. I remember that Ancient Briton chief as if it were yesterday. Love chariot reins. Keep up the good fight!

Had a couple of sets. Discovered that my Dad's gloss door paint stuck to these figures like glue - mind you it was a bit on the thick side and remember that I painted my archers robes in an amazing deep yellow gloss and their helmets were a kind of burgundy colour. Those archers were and still are my favourite figs in this set. In my battles they downed many a World War 1 German infantryman as well as French Cuirassier as well as their more correct Ancient Briton adversaries. I remember that Ancient Briton chief as if it were yesterday. Love chariot reins. Keep up the good fight!

Had a couple of sets. Discovered that my Dad's gloss door paint stuck to these figures like glue - mind you it was a bit on the thick side and remember that I painted my archers robes in an amazing deep yellow gloss and their helmets were a kind of burgundy colour. Those archers were and still are my favourite figs in this set. In my battles they downed many a World War 1 German infantryman as well as French Cuirassier as well as their more correct Ancient Briton adversaries. I remember that Ancient Briton chief as if it were yesterday. Love chariot reins. Keep up the good fight!-

k.b.

- Posts: 1136

- Member since:

04 Apr 2010, 03:50

Hi Ironsides - for some reason this post has been split - I answered but it is on the other thread (or part of this thread - very confusing!)

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

The stele has a number of unusual features; firstly it shows a fully armoured legionary whereas most steles show legionaries with weapons but not in armour. Secondly it has (literally) been defaced - apparently indicating that he (or his family) were out of favour. Lastly the inscription says he belongs to a clan that had apparently died out by this time.

So perhaps a bit of a mystery here.

So perhaps a bit of a mystery here.

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

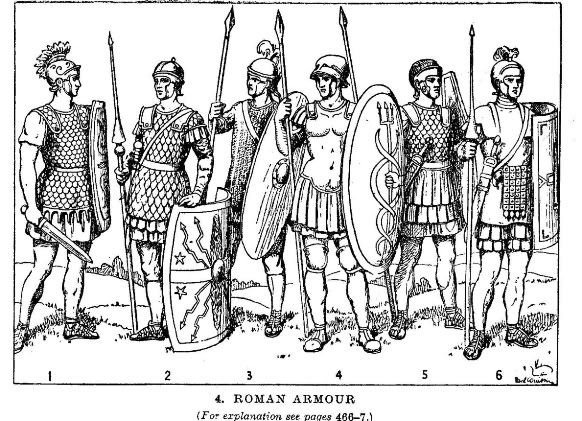

Earliest interpretation of G.Valerius Crispus I know is in Coussin, Les Armes. Romaines, 1924, (chappie on far right):

Amedee Forestier did a version in The Roman Soldier, 1928, described as an auxiliary, IIRC (was one of my favourite books when I was a kid, on repeated loan from the local library - not, I hasten to add, in 1928...)

A further version appeared in Funcken Le costume et les armes des soldats de tous les temps, 1966, which I'll try to scan later, if this works - first time I've used this Botophucket thingie...

Latest appearance is on the cover of D’Amato Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Arms-Armour-Imp ... 1848325126

Again with leather armour, but that is a whole new different can of vermicelli…

Mike

B***** me, it actually seems to have worked! All I've got to do now is work out the size factor...

Amedee Forestier did a version in The Roman Soldier, 1928, described as an auxiliary, IIRC (was one of my favourite books when I was a kid, on repeated loan from the local library - not, I hasten to add, in 1928...)

A further version appeared in Funcken Le costume et les armes des soldats de tous les temps, 1966, which I'll try to scan later, if this works - first time I've used this Botophucket thingie...

Latest appearance is on the cover of D’Amato Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Arms-Armour-Imp ... 1848325126

Again with leather armour, but that is a whole new different can of vermicelli…

Mike

B***** me, it actually seems to have worked! All I've got to do now is work out the size factor...

-

bilsonius

- Posts: 661

- Member since:

08 Feb 2009, 02:31

While I'm on a roll, here's the 1966 Funcken, with our Gaius playing on the left wing again, described as "légionnaire, portant la cuirasse articulée et le scutum rectangulaire":

By Jove, this old fart is actually starting to get the hang of all this modern technology

(Bought the book on a school exchange visit long ago last century. It's a bit dated, but still has a certain charm, and great sentimental value...)

Mike

By Jove, this old fart is actually starting to get the hang of all this modern technology

(Bought the book on a school exchange visit long ago last century. It's a bit dated, but still has a certain charm, and great sentimental value...)

Mike

-

bilsonius

- Posts: 661

- Member since:

08 Feb 2009, 02:31

Help keep the forum online!

or become a supporting member

Well done Bilsonius! I well know the satisfaction from mastering new technology (though I've still not mastered texting).

Any chance of reposting your figure from Les Armes. Romaines as it is too small to make much out.

One thing that struck me was that the Airfix figures are not influenced by the Funcken book as I had presumed as they predate its publication. So the Airfix sculptors were either working from those much earlier books or from the stele (though the latter would seem unlikely). Does the Les Armes. Romaines show a Syrian archer and a centurion with a rounded shield I wonder?

All the best

Douglas

Any chance of reposting your figure from Les Armes. Romaines as it is too small to make much out.

One thing that struck me was that the Airfix figures are not influenced by the Funcken book as I had presumed as they predate its publication. So the Airfix sculptors were either working from those much earlier books or from the stele (though the latter would seem unlikely). Does the Les Armes. Romaines show a Syrian archer and a centurion with a rounded shield I wonder?

All the best

Douglas

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

That seems better; the first time I posted this one it seemed far too big, so I must have over-compensated - not as WYSIWYG as I thought. My copy of this illustration is from the Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, 1959 edition, but first printed in 1938. The caption, from Coussin, is "[1st century AD] legionary: Attic-Roman helmet of the Weisenau type; leather coat, probably with a coat of mail underneath it; fringed breeches; Iberian sword, cross belt; cingulum militiae; pilum reinforced by metal cone."

There is reference to the Crispus monument here in Roman Army Talk website (second-last post on page):

http://www.romanarmytalk.com/rat/viewto ... 39&start=0

There are no archers at all in the Roman section of Funcken, or any equivalent of the other Airfix figs, but I can (!!!) post scans of the full pages if anyone's interested...

Mike

-

bilsonius

- Posts: 661

- Member since:

08 Feb 2009, 02:31

-

The Observer - Posts: 665

- Member since:

11 May 2009, 21:31

Tell a fib - the Funcken predates the Airfix set by a year so could have been the inspiration for the Airfix set. But where does the archer come from if not from Funcken?

I agree that interpreting the body armour as being leather is a bit of a leap - I think the interpretation of leather is just because it doesn't look like chain mail rather than any positive reason.

I'm still totally unconvinced by those shorts. There are pteruges at the shoulders so, unless the soldiers are wearing two under garments, the undergarment would be a bit like an old fashioned male bathing costume where you would have to step into the trousers first before pulling it up and putting your arms through the arm holes and presumably lacing the whole thing up at the back (or front). So much easier if the whole thing is like a kilt and is just pulled on over the head.

The stele is a real puzzle as the shield is apparently so accurate but everything else is pretty weird. Very influential though.

I agree that interpreting the body armour as being leather is a bit of a leap - I think the interpretation of leather is just because it doesn't look like chain mail rather than any positive reason.

I'm still totally unconvinced by those shorts. There are pteruges at the shoulders so, unless the soldiers are wearing two under garments, the undergarment would be a bit like an old fashioned male bathing costume where you would have to step into the trousers first before pulling it up and putting your arms through the arm holes and presumably lacing the whole thing up at the back (or front). So much easier if the whole thing is like a kilt and is just pulled on over the head.

The stele is a real puzzle as the shield is apparently so accurate but everything else is pretty weird. Very influential though.

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

Just got the D'Amato-Sumner Roman Soldier from the City Library - must have been ordered before all the budget cuts were announced!

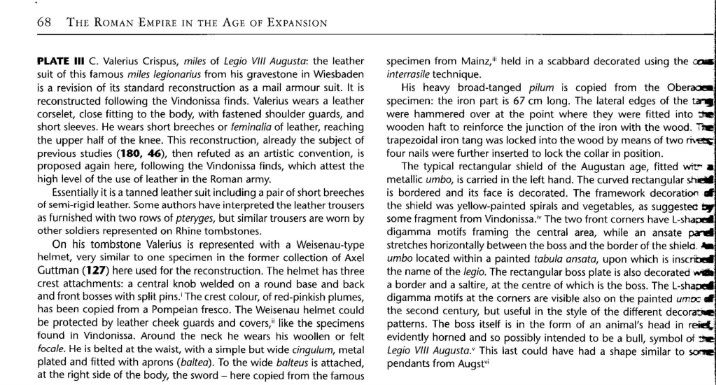

FWIW, this is the caption for the G. Valerius Crispus illustration also shown on the cover (and viewable in previous posts):

I think the right hand margin is just about legible - couldn't get it any better without damaging either the book or my scanner... Don't think I'm infringing copyright with short non-profit extract for academic discussion

The book is actually quite impressive and fascinating, and it's going to take me several library renewals to work through it. If you think our Gaius is a bit unorthodox compared with conventional legionary reconstructions, you should see some of the other guys...

Valete, pro tem.

Mike

FWIW, this is the caption for the G. Valerius Crispus illustration also shown on the cover (and viewable in previous posts):

I think the right hand margin is just about legible - couldn't get it any better without damaging either the book or my scanner... Don't think I'm infringing copyright with short non-profit extract for academic discussion

The book is actually quite impressive and fascinating, and it's going to take me several library renewals to work through it. If you think our Gaius is a bit unorthodox compared with conventional legionary reconstructions, you should see some of the other guys...

Valete, pro tem.

Mike

-

bilsonius

- Posts: 661

- Member since:

08 Feb 2009, 02:31

Thanks for posting the relevant bit from the D'Amato-Sumner book. (a quick aside about copyright - in the UK at least you are allowed to copy sections of published works for personal use but you are not allowed to copy a whole book. Thus you are not in breach of copyright by posting short sections. I'm sure you will sleep at night now!).

The D/S book has of course come in for a lot of flak. There is a lot of quite dismissive comment on Roman Army talk, including of this particular reconstruction. There are really two issues here: the interpretation of the lorica as being leather and the lederhosen.

I don't want to rehash all of the argument on RAT but would just point to the assertion that there isn't ANY unequivocal archaeological evidence for leather lorica despite leather finds from Roman remains being relatively common. Metal armour is frequently found but not leather (though boots, fastening etc are frequently also found). It would thus seem unlikely that leather was used as armour. It probably was used as sub-armata ie the clothing under the armour. However, the shoulder guards on the stele suggest that this is not a sub armata. Most probably it is to represent mail. I was reminded that steles were painted and the artist may have represented the mail by painting it on rather than sculpting.

None of that is to claim that leather has never been used as armour just that there is no real evidence of the Romans doing it.

As for the lederhosen - you made me laugh by suggesting that this represents the first evolution of the lederhosen! I have no problem with these being shorts rather than pteruges. We know that legionaries began to wear shorts in the later Empire and I too am intrigued by the comment that these are common on other steles from this area. I still cannot see how they would connect with the shoulder pteruges and I can't think of why they should have this peculiar surface - or at least I cannot think of a functional reason. I still think that the artist may have been confusing the shorts with pterurges and hence the rather peculiar appearance but it will be much more convincing if more steles show this appearance.

The D/S book has of course come in for a lot of flak. There is a lot of quite dismissive comment on Roman Army talk, including of this particular reconstruction. There are really two issues here: the interpretation of the lorica as being leather and the lederhosen.

I don't want to rehash all of the argument on RAT but would just point to the assertion that there isn't ANY unequivocal archaeological evidence for leather lorica despite leather finds from Roman remains being relatively common. Metal armour is frequently found but not leather (though boots, fastening etc are frequently also found). It would thus seem unlikely that leather was used as armour. It probably was used as sub-armata ie the clothing under the armour. However, the shoulder guards on the stele suggest that this is not a sub armata. Most probably it is to represent mail. I was reminded that steles were painted and the artist may have represented the mail by painting it on rather than sculpting.

None of that is to claim that leather has never been used as armour just that there is no real evidence of the Romans doing it.

As for the lederhosen - you made me laugh by suggesting that this represents the first evolution of the lederhosen! I have no problem with these being shorts rather than pteruges. We know that legionaries began to wear shorts in the later Empire and I too am intrigued by the comment that these are common on other steles from this area. I still cannot see how they would connect with the shoulder pteruges and I can't think of why they should have this peculiar surface - or at least I cannot think of a functional reason. I still think that the artist may have been confusing the shorts with pterurges and hence the rather peculiar appearance but it will be much more convincing if more steles show this appearance.

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

Sorry for the delay in getting back to this.

I've copied a recent review of the D'Amato book below which is quite interesting.

Regarding leather armour: leather has been used for armour by various cultures, including ones contemporary with the Romans so why shouldn't the Romans have used leather armour? Probably best reason is that leather needs to be much thicker and more inflexible than metal armours to achive the same degree of protection. If you think about the three main forms of Roman armour: scale, chain and segmented, they are all flexible to a degree that isn't possible for leather. Since the Roman soldier was equipped by the State it made sense to equip its soldiers with the best armour it could afford - which was metal (though fabric may have been used in very hot districts).

Basically, if you could get metal armour you would use it in preference to leather as the latter has no advantages (other than perhaps price) over metal armour. The Romans were able to manufacture plenty of metal armour so don't seem to have bothered with leather for armour (they used leather for plenty of other things though - including pteruges.

The argument about horse armour is different - it's not clear how much horse harness is actually armour as opposed to be for decoration and it may also be that as cavalry were so much less important than the infantry that there was not the same availability of metal horse armour that there was for the men.

The nature of the cuirass is of course open to debate. Officers didn't really need to get stuck in (or when they did it was probably because the battle was lost anyway so the protective properties of their armour may have been less important as they weren't expecting to survive!). They may have used leather cuirasses as a lighter weight (but definitely inferior) alternative to the bronze version. It is interesting that centurions never seemed to have used the cuirass and I don't think this is just a class thing. So I'm prepared to imagine that leather might have been used for the cuirass (though I'm unaware of any having being found).

The review makes the important point that archaeological finds are more important that funerary and other representations as they offer tangible evidence of a real product rather than a representation of one:

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2010.09.49I suspect many will be aware of this book, however, the review may be useful.

I've copied a recent review of the D'Amato book below which is quite interesting.

Regarding leather armour: leather has been used for armour by various cultures, including ones contemporary with the Romans so why shouldn't the Romans have used leather armour? Probably best reason is that leather needs to be much thicker and more inflexible than metal armours to achive the same degree of protection. If you think about the three main forms of Roman armour: scale, chain and segmented, they are all flexible to a degree that isn't possible for leather. Since the Roman soldier was equipped by the State it made sense to equip its soldiers with the best armour it could afford - which was metal (though fabric may have been used in very hot districts).

Basically, if you could get metal armour you would use it in preference to leather as the latter has no advantages (other than perhaps price) over metal armour. The Romans were able to manufacture plenty of metal armour so don't seem to have bothered with leather for armour (they used leather for plenty of other things though - including pteruges.

The argument about horse armour is different - it's not clear how much horse harness is actually armour as opposed to be for decoration and it may also be that as cavalry were so much less important than the infantry that there was not the same availability of metal horse armour that there was for the men.

The nature of the cuirass is of course open to debate. Officers didn't really need to get stuck in (or when they did it was probably because the battle was lost anyway so the protective properties of their armour may have been less important as they weren't expecting to survive!). They may have used leather cuirasses as a lighter weight (but definitely inferior) alternative to the bronze version. It is interesting that centurions never seemed to have used the cuirass and I don't think this is just a class thing. So I'm prepared to imagine that leather might have been used for the cuirass (though I'm unaware of any having being found).

The review makes the important point that archaeological finds are more important that funerary and other representations as they offer tangible evidence of a real product rather than a representation of one:

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2010.09.49I suspect many will be aware of this book, however, the review may be useful.

From: Bryn Mawr Classical Review

Sent: Tuesday, September 28, 2010 9:01 AM

To: nikgaukroger@blueyonder.co.uk

Subject: BMCR 2010.09.49: Levithan on D'Amato, Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2010.09.49

----------------------------------------------------------

Raffaele D'Amato, Graham Sumner, Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier: From Marius to Commodus, 112 BC-AD 192. London: Frontline, 2009. Pp. xiv, 290. ISBN 9781848325128. $60.00.

----------------------------------------------------------

Reviewed by Josh Levithan, Kenyon College (levithanj@kenyon.edu)

The first published and chronologically central of a projected three volumes, this is a large and generously illustrated bid for “definitive†status in the field of Roman military equipment studies. This bid seems unlikely to succeed, given the greater ease-of-use and archaeologically-grounded sobriety of M.C. Bishop and J.C.N. Coulston’s Roman Military Equipment (second edition: Oxbow, 2006). This book is, however, in many ways an impressive achievement, a testament to an enormous scholarly effort—and it is a significant contribution to the understanding of the Roman army. Yet the effort is almost more antiquarian than scholarly. D’Amato (responsible for the main text and many photographs; the introduction and the new paintings and drawings are by Sumner) brings to bear his considerable expertise in the physical and representational evidence for Roman arms and armor, and he has most assuredly done his homework, travelling to many far-flung monuments and museums in order to photograph less-well-known artifacts. But the book is more successful as a compendium than as a balanced advancing-of-our-knowledge- work.

The prolific illustration is both a major strength and a weakness of the book, but the text does not always do much to support the author’s assertion of a “radically different†interpretation of his subject, namely that the representational evidence on surviving monuments is realistic and accurate, and thus a better route to re-imagining the army than keeping largely to the archaeological remains. In the introduction, Sumner asserts that “the purpose of this work is to throw new light on the examination of the equipment, armour, and clothing of the Roman soldier.†In this D’Amato and Sumner are largely successful, but the light is indeed thrown about, rather than focused. D’Amato repeatedly declares his belief that the representational monuments are highly accurate, but he seems aware that this is a subjective commitment, and he repeatedly hedges his bets: monuments and gravestones were merely “linked†to “the rigid necessity of realism†(xiii); relief sculptures “could be considered†as “something like†sketches from life or “modern photographic reportage.†They could; but it is hard to fault those who prefer to base their understanding of Roman arms and armor on the surviving artifacts, however incomplete that picture remains. This new Arms and Armour is exhaustive in its coverage of armor and weapon types, and D’Amato adduces good literary evidence to supplement the physical. He does indeed have new evidence to present even on object-types that have drawn much attention in recent decades from both archaeologists and serious re-enactors. But the quirks of this book hamper both its effectiveness as a scholarly treatise and its usefulness as a reference work. Divided into only two chronological sections (around the year 30 BCE) and then subdivided by arm of service, the actual discussion of the categories of objects is fragmented—it is a poor compromise between diachronic explanation and item-by-item comprehensiveness. The three bits at the beginning of each of the two major sections—a paragraph-shaped list of sources, an “events timeline,†and a few columns on military organization—are far too condensed to be of much use. The page-by-page layout is also rather odd: running descriptions of objects are interspersed with monument-by-monument photographs that do not all that often correspond to the accompanying text. There is an enormous amount of material here, but it takes patience (and five or six cross-referencing fingers jammed into various parts of the book, including the endnotes), to bring all the evidence to bear. This is particularly true if one is interested in, for example, a sword type that might have seen use by both infantry and cavalry across several centuries.

Despite occasional awkwardness in the prose, the descriptive passages are generally clear, but the short introductory passages to the new object categories can be somewhat obscure. There are some curious assertions of personal preference, such as referring to “the Consular age†rather than “the Republic,†but a more problematic choice is that several interpretive stances are boldly asserted, but not closely argued. One example of this is the discussion of representational accuracy on pages 66-7, where D’Amato argues that the presence of Apollodorus of Damascus on Trajan’s Dacian campaigns means that the scenes on Trajan’s column were taken from life, and thus depict Roman equipment in a realistic manner. Yet he acknowledges that the consistent portrayal of legionaries and auxiliaries in different armor types was probably a matter of artistic preference, obscuring a less uniform reality. The careful uncertainty of other scholars of the column seems to be the better position.

When it comes to details, D’Amato’s arguments are generally either convincing or beyond this reviewer’s ability to assess—but on the big questions he is generally not persuasive. That “the concept of parade armour or helmets [sic] did not exist in the ancient world†(xiv) is, at best, debatable; but the idea that the usual description of certain decorated and masked helmets as parade or sporting equipment that was not used in actual combat “should definitely be rejected†(187) is untenable. The weakness of D’Amato’s argument at this point is glaring. There is an unsupported simple assertion (“it is absolutely contrary to the ideology of the ancient warriorâ€), a bit of circumstantial evidence (some so-called “sports helmets†have been found in graves together with battle equipment), and an appeal to the psychological impact of impressive looking weapons. This impact was certainly important (and has been much discussed in the last two decades), but it is very strange indeed that the quotation offered as evidence of this effect (from Josephus, Bellum Judaicum, V, 350ff) describes soldiers taking their impressive armor and equipment out of cases during a days-long lull in the fighting, and putting it on for the express purpose of a parade.

Both the quality and quantity of the illustration are worth a few words more. The kitchen sink approach to illustration can be overwhelming, but it will present even a dedicated aficionado of Roman arms and armor with new images. The paintings too are surprisingly effective. Rather than the loosely imagined scenes that are now common in books on the Roman military, these are useful restoration studies. Sumner has in effect painted “cover†versions of extant funerary monuments, in which the restoration of color and detail enhances the interest of the original carving. These paintings are tied directly to descriptive commentary on the facing page, usually accompanied by a photograph of the monument, that details literary and archaeological support for the painting. These facing pages, too, have footnotes (rather than endnotes), so that that source, the argument of reconstruction, and the image can be taken in without turning the page.

In contrast to the paintings, many pages are overcrowded with many small photographs of in situ reliefs. Given that conditions obviously limited the quality of many images, these pages can be very hard to read. Other photographs are unreasonably small: it’s hard to know what to do with three 2-by-2 3/4-inch photos of the same heavily-weathered, greave-bearing legs, or with the seventeen adjacent photographs of “metopae reliefs from Munatius Plancus’ mausoleum†(23). In an age when most of us are nearly as accustomed to reading on the internet as in a book, one has the odd sensation of wanting to “click†on printed “thumbnails†in the hopes of significantly enlarging them. But to no avail—the weather-blurred legs, shields, and scabbard fittings are all we get.

Other photographs, however, are more valuable, providing clear evidence that Roman army books have been complacently drawing on the same pool of images for too long. One pleasant surprise is the Arch of Carpentras (which seems to have attracted little scholarly attention in the last century, although it is discussed in C. Antonucci’s L’esercito di Cesare and, naturally, can be found on Wikipedia). One face of the arch depicts two figures posed beside an oddly-rendered trophy, exotic weapons at their feet. The use of this monument is a good example of the too-intense focus on detail which is common to this sub-field and perhaps a particular fault of this book. D’Amato carefully considers the evidence for the late Republican scabbard shape, and the facing page includes twelve tiny photos of the three scabbards shown on the relief. Since the relief is being presented as realistic representational evidence for Roman arms, it should be worth noting that the figures appear to be non-Roman captives, and that it might not immediately be clear why Roman-seeming swords should be hanging on the trophy between them. Can even a reader disinclined to appeal to the expertise of art historians treat these images as evidence without some consideration of context or techniques of representation?

D’Amato acknowledges his debt to M.C. Bishop, in particular, and engages him in a good deal of recondite debate about the details of certain objects (particularly the segmented armor of the imperial legionary). It is generally rather difficult for a non-specialist, even one knowledgeable about the army in general, to distinguish between minor quibbles, essential agreements, and truly vexed questions, but anyone concerned with the possible omission of lobate hinges from some specimens of Stillfried-type lorica segmentata will need to consult both books.

There are some improvements, too, on Bishop and Coulston: the representational evidence is much more complete (Bishop and Coulston make little use of it after an initial short chapter on the subject), and there is more detailed discussion of certain objects, in particular organic materials (leather and linen worn either as armor or underneath it). D’Amato collects a great deal of rare evidence on this little-discussed subject, but it is still a sketchy collection, and nearly every paragraph of the argument that such materials are more important than metal-based reconstructions acknowledge must lapse into the subjunctive. There is irony in the fact that his most extensive use of archaeological evidence involves metal weapons, to supplement the photographs of monuments from which the metal detailing that once represented spear points and other weapons have long since been removed.

In many respects the two publications are complementary, with D’Amato and Sumner relying more on the representational evidence and Bishop and Coulston on archaeology—but the reasons for preferring Bishop and Coulston are clear. First, it is not quite time for a pseudo-revisionist return to the sculpture-inspired, antiquarian way of envisioning the Roman army. Even if some of the monuments here had slipped from the radar of modern scholarship, and even if the increasingly dominant images of meticulously tricked-out re-enactors are derived from the physical remains of armor and weapons, the images from a few famous monuments still retain their fundamental influence on modern imaginings of the Roman soldier. Second, this is not really a simple choice between equally valid methods. The representational evidence will never be completely free of the question of “accurate†depiction by the ancient artists, while the archaeological survivals offer, in most cases, significantly more secure starting places for re-creation. Finally, Bishop and Coulston provide a balanced analysis of the artifacts that is more in keeping with the tenor of recent scholarship, and their book is better indexed and easier to use. At the very least, that one volume, available in paperback and a more secure choice as a reference (both in terms of representing the consensus of Roman military archaeologists and in not including full-color, full-page illustrations of severed-head-bearing cavalrymen) will remain a more realistic choice of Roman historians than this large volume and its two projected successors.

D’Amato is to be congratulated on the effort and expertise that went into this book, and he will earn the thanks of many dedicated students of the Roman army for bringing so much rare material to their attention. It seems likely that this reinfusion of certain monuments—and perhaps also of his faith in their representational reality—into the debate will stimulate further discussion, and if it does so, his book should be counted a scholarly success as well as an antiquarian achievement.

-

Tantallon2

- Posts: 1140

- Member since:

16 Nov 2009, 23:24

13 posts

• Page 1 of 1